Introduction to Bermuda SBA Modeling: Part 1

In February and July 2023, the Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) released two consultation papers (CP) (commonly referred to as “CP1” and “CP2”) regarding the “Proposed Enhancements to the Regulatory Regime for Commercial Insurers.” These CPs included changes to the calculation and modeling of Bermuda’s economic balance sheet (EBS) that are now included in the revised prudential standards today.

With this article, we provide an overview of the EBS financial reporting requirements with a focus on the considerations specific to scenario-based approach (SBA) models.

For individuals unfamiliar with SBA modeling or Bermuda reinsurance, our article provides practical insights. Aimed at modeling actuaries, our content breaks down complexities to offer a clear understanding of SBA modeling under the Bermuda reinsurance landscape.

Bermuda EBS overview

For readers unfamiliar with Bermuda EBS, this section provides an overview of the framework. Readers familiar with this topic may skip this section and move on to the modeling considerations.

Bermuda EBS[1]

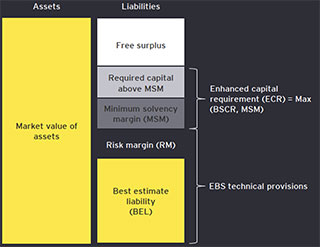

Figure 1 below is an overview of the Bermuda EBS capital framework for long-term life insurers. EBS reserves are calculated based on a market-consistent approach, meaning that liabilities should be valued using market data where possible to reflect the current financial environment. The EBS framework promotes an economic view of the insurer’s balance sheet, meaning that assets and liabilities should reflect real economic conditions. The philosophy underlying the EBS framework also emphasizes the need for transparency in calculations and methodologies, allowing the BMA and other stakeholders to compare insurers’ solvency positions across the market.

Figure 1

Overview of the Bermuda EBS Capital Framework for Long-Term Life Insurers

- The EBS technical provision is established as the sum of the best-estimate liability (BEL) and the risk margin (RM).

- The BEL represents the present value of best-estimate cash flows (i.e., without prudency margins or PADs as commonly referred to under US GAAP). This can be calculated using either the standard approach (SA) or the SBA. Note that the SBA includes certain requirements that must be met (such as reasonable liability and asset cash flow matching) and additional approvals to be provided by the BMA.[2]

- The RM represents an additional margin associated with uncertainty in liability cash flows (comparable in certain respects to a PAD) and is typically determined using a cost-of-capital approach.

- The ECR is the maximum of the Bermuda solvency capital requirements (BSCR) and the minimum solvency margin (MSM).

The BEL is typically a material part of the liability side of the balance sheet, and, depending on the product, the calculation of other balance sheet components may rely on it. As mentioned above, this article is focused on the BEL due to its modeling complexities.

EBS BEL

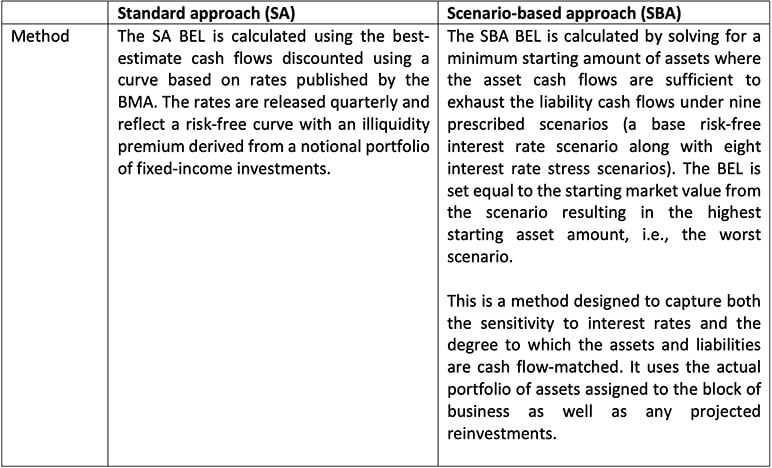

Under the Bermuda EBS framework, there are typically two approaches to calculating the BEL: The standard approach (SA) and the SBA. Both methods are founded on best-estimate cash flow projections, account for the probability-weighted average of all future cash flows, and are based on best-estimate assumptions developed using relevant, credible experience as well as expert judgment regarding future trends and developments. (See Table 1)

Table 1

SA versus SBA Comparison

Given its simplicity, the SA does not pose significant modeling challenges, and thus the remainder of this article is focused on SBA modeling considerations.

SBA Modeling Considerations

This section covers six modeling considerations for SBA:

- Assets and reinvestment,

- stress testing,

- solving for starting asset marketing value,

- model validation,

- forecasting, and

- integration with existing models.

Considerations 4 through 6 will be covered in Part 2 of this series.

1. Modeling Assets and Reinvestment

Modeling assets under the SBA calculation involves accurately modeling complex asset classes. Reinvestment modeling requires a highly robust asset model, oftentimes with clear asset segmentation and prioritization to maintain balance. This may involve selling assets and aligning different reinvestment/divestment approaches to Bermuda and to the company’s own strategy. Companies must model the market value under the SBA. Accurate market value calculations for structured assets are essential to capturing the cash flows generated from selling/buying assets, which allow for defaults, downgrades and transaction costs.

Modeling Assets

Within the SBA calculation, there is increased focus on accuracy in asset modeling since it directly translates into impact on the BEL (and thus reserves). US insurers building modeling capabilities to support offshore reinsurance will likely have to manage modeling challenges that are due to the increased allocation to more complex asset classes, which may increase the need to either model these asset classes within the actuarial system or rely on externally projected assets (EPAs), which brings its own complications.

While it may be common to use asset-specific modeling platforms and EPAs, granularity and the aggregation of EPAs may introduce data-related challenges when processing the projected asset cash flows in the downstream SBA calculation to effectively capture the appropriate purchases and sales of assets.

Another asset-related challenge for modeling actuaries can occur when supporting new deals, which may often be for a Bermuda reinsurance company or affiliate. Companies may need to explore the use of new asset classes in a short time frame. It may require the modeling actuary to quickly implement and test new asset classes or develop approximations.

Modeling Reinvestment and Disinvestment

In Bermuda, reinvestment and disinvestments require asset segmentation and prioritization in order to maintain a balanced portfolio that fits within the investment guidelines and the SBA eligibility requirements. Decisions need to be made on selling eligible assets proportionally or based on other factors (e.g., liquidity, duration). The latter requires the categorization of existing and reinvestment assets, which itself may require computation (e.g., for duration) at each timestep. One consideration is to optimize the reinvestment frequency to manage runtime. Furthermore, this requires tracking of assets at a granular level to accurately capture sales or reinvestments for future timesteps.

The Bermuda valuation standard does not allow borrowing or negative cash flows; therefore, it requires modeling of the sale of assets along the projection to satisfy liability cash flows. This requirement may introduce inconsistency with the asset-liability modeling methodology used for US financial reporting and internal analysis, which may allow borrowing and maintaining a negative cash balance. It will also increase the importance of accurate market value calculations for structured assets and transaction costs.

2. Stress Testing

The 2023 consultation papers also described specific tests to be performed for the SBA model. This section discusses some considerations related to SBA modeling introduced by the CPs.

One-Notch Downgrade

The one-notch downgrade stress test is required under CP2 for new applications. The test assumes a mass reduction in the credit worthiness of assets backing a line of business. The in-force asset portfolio and market value need to be adjusted to reflect reduced asset ratings by one notch (e.g., BBB to BBB-), with adjusted default rates and spreads to reflect the heightened risk. After the downgrade, assets may fall below investment grade and should not be included in SBA calculation. These securities could be removed from the asset portfolio in an SBA model.

Credit Spread Widening

The credit spread widening stress test is required under CP2 for new applications. The test increases the spread over risk-free rates for the first calendar year only, which may be limited to the out-of-box capability of the actuarial platform and could require creative modeling approaches. If the out-of-box functionality of the SBA model does not support the first-year credit stress, the model may need to be customized to accommodate such a test. Alternatively, the stress may be applied externally and supplied via the model inputs such as scenario files.

3. Solving for the Starting Asset Market Value

In SBA modeling, we aim to solve for the starting asset market value to achieve an ending market value of 0 at the end of the projection period, and to ultimately extinguish the liability cash flows. This iterative process could have significant runtime implications and become especially significant for interest-sensitive assets and liabilities, especially when the SBA modeling platform is not equipped with out-of-box goal-seeking functionality.

Solving for a Factor

To achieve this, the model may solve for a factor of the starting asset market value. This factor would fall between 0 and 1 if the in-force assets are sufficient. A factor greater than one indicates that the in-force assets are not sufficient to cover the liabilities and additional assets are needed to support the future liability cash flows. To evaluate the BEL for a new business block not yet issued where an existing asset portfolio is not yet available, the model may solve for a starting cash amount at issue and immediately reinvest; other modeling options include construction of a proxy portfolio for the new business and solving for the starting factor, similar to an in-force block.

Process Considerations

In practice, there are various ways for in- or out-of-model processing for the iterative solving. Within the calculation engine itself, if out-of-box functionality is not available from the actuarial modeling platform, one can customize the model and implement iterative methods (e.g., Lagrange multiplier) to solve for the asset scalar. Out-of-model adjustments may be used for batch runs utilizing Excel and model APIs that iteratively change model inputs (e.g., asset scalars), to kick off new model runs and to interpolate model results to find a solution.

Additional Runtime Considerations

Depending on the calculation method and actuarial platform, there may be some additional considerations while solving for the starting market value:

- Depending on the product feature, the in-force and reinvestment assets modeled, and the solving mechanism, the number of iterations needed to find a scalar may vary. This also impacts the model runtime. We have observed that it is generally harder to match liability and asset cash flows for products with longer periods of benefit cash flows (i.e., longer projection in model) or for smaller asset portfolios with a handful of CUSIPs. Selecting initial guesses based on prior similar runs or increasing the number of CUSIPs with varying durations would help with reaching convergence more easily.

- For interest-sensitive products where dynamic lapses and/or crediting rates are affected by portfolio rates, assets and liabilities would have to be reprojected and would further impact runtime. Based on our observation, an alternative modeling approach such as using externally projected liabilities (EPL) or competitor rates (instead of portfolio earn rates) would help reduce runtime.

Stay tuned for the next installment of our two-part series as we continue to discuss the considerations for SBA modeling, specifically around model validation, forecasting and integration with existing models.

The views reflected in this article are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ernst & Young LLP or other members of the global EY organization, the Society of Actuaries, the newsletter editors, or the respective authors’ employers.